George

Eastman

George Eastman (July 12, 1854 Ð March 14,1932)

was an inventor in the photography field, specifically the invention of

photographic film to replace photographic plates, thus leading to the

technology used by film cameras prevalent in the 20th Century. I'm confident he would have marveled

at the digital revolution dominant in the 21st Century. He was one of the founders of Eastman-Kodak Company. Unfortunately, the company essentially

went out of business in the early 2000's, continuing only in a small niche of

the market.

George is

the sixth great grandson of Plymouth Colony Governor

William Bradford, who is my sevnth

great grandfather.

George is the sixth cousin, once removed to me. He is a sixth cousin, once removed to

my son-in-law, Steven O. Westmoreland.

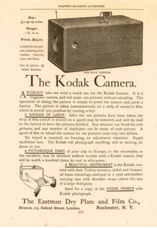

George

Eastman was an ingenious man who contributed greatly to the field of

photography. He developed dry

plates, film with flexible backing, roll holders for the flexible film, a Kodak

camera (a convenient form of the camera for novices), and an amateur motion-picture

camera. Through his experimental

photography, he accumulated a large sum of money. His philanthropic personality

prompted him to give his money to various business endeavors, including the

University of Rochester.

He was a

high school dropout, judged 'not especially gifted' when measured against the

academic standards of the day. He

was poor, but even as a young man, he took it upon himself to support his

widowed mother and two sisters, one of whom was severely handicapped.

He began his

business career as a 14-year old office boy in an insurance company and

followed that with work as a clerk in a local bank.

He was

George Eastman, and his ability to overcome financial adversity, his gift for

organization and management, and his lively and inventive mind made him a

successful entrepreneur by his mid-twenties, and enabled him to direct his

Eastman Kodak Company to the forefront of American industry.

But building

a multinational corporation and emerging as one of the nation's most important

industrialists required dedication and sacrifice. It did not come easily.

The youngest

of three children, George Eastman was born to Maria Kilbourn

and George Washington Eastman on July 12, 1854 in the village of Waterville, some 20 miles southwest of

Utica, in upstate New York. The

house on the old Eastman homestead, where his father was born and where George

spent his early years, has since been moved to the Genesee Country Museum in

Mumford, N.Y., outside of Rochester.

When George

was five years old, his father sold his nursery business and moved the family

to Rochester. There the elder

Eastman devoted his energy to establishing Eastman Commercial College. Then tragedy struck. George's father died, the college

failed and the family became financially distressed.

George

continued school until he was 14. Then,

forced by family circumstances, he had to find employment.

His first

job, as a messenger boy with an insurance firm, paid $3 a week. A year later, he became office boy

for another insurance firm. Through

his own initiative, he soon took charge of policy filing and even wrote

policies. His pay increased to

$5 per week.

But, even

with that increase, his income was not enough to meet family expenses. He studied accounting at home

evenings to get a better paying job.

In 1874,

after five years in the insurance business, he was hired as a junior clerk at

the Rochester Savings Bank. His salary tripled -- to

more than $15 a week.

When Eastman

was 24, he made plans for a vacation to Santo Domingo. When

a co-worker suggested he make a record of the trip, Eastman bought a

photographic outfit with all the paraphernalia of the wet plate days.

The camera

was as big as a microwave oven and needed a heavy tripod. And he carried a tent so that he

could spread photographic emulsion on glass plates before exposing them, and

develop the exposed plates before they dried out. There were chemicals, glass tanks, a

heavy plate holder, and a jug of water.

The complete outfit was a pack-horse load, as he described it. Learning how to use it to take

pictures cost $5.

Eastman did

not make the Santo Domingo trip. But he did become completely absorbed in

photography and sought to simplify the complicated process.

He read in

British magazines that photographers were making their own gelatin emulsions. Plates coated with this emulsion

remained sensitive after they were dry and could be exposed at leisure. Using a formula taken from one of

these British journals, Eastman began making gelatin emulsions.

He worked at

the bank during the day and experimented at home in his mother's kitchen at

night. His mother said that some nights Eastman was so tired he couldn't undress,

but slept on a blanket on the floor beside the kitchen stove.

After three

years of photographic experiments, Eastman had a formula that worked. By 1880, he had not only invented a

dry plate formula, but had patented a machine for preparing large numbers of

the plates. He quickly

recognized the possibilities of making dry plates for sale to other

photographers.

In April

1880, Eastman leased the third floor of a building on State Street in

Rochester, and began to manufacture dry plates for sale. One of his first purchases was a

second-hand engine priced at $125.

'I really needed only a one horse-power,'

he later recalled. 'This was a two horse-power, but I thought perhaps business

would grow up to it. It was

worth a chance, so I took it.'

As his young

company grew, it faced total collapse at least once when dry plates in the

hands of dealers went bad. Eastman

recalled them and replaced them with a good product. 'Making good on those

plates took our last dollar,' he said. 'But what we had left was more important

--reputation.'

'The idea gradually dawned on me,' he

later said, 'that what we were redoing was not merely making dry plates, but

that we were starting out to make photography an everyday affair.' Or as he described it more succinctly

'to make the camera as convenient as the pencil.'

Eastman's

experiments were directed to the use of a lighter and more flexible support

than glass. His first approach

was to coat the photographic emulsion on paper and then load the paper in a

roll holder. The holder was used

in view cameras in place of the holders for glass plates.

The first

film advertisements in 1885 stated that shortly there will be introduced a new

sensitive film which, it is believed, will prove an economical and convenient

substitute for glass dry plates both for outdoor and studio work.

This system

of photography using roll holders was immediately successful. However, paper was not entirely

satisfactory as a carrier for the emulsion, because the grain of the paper was

likely to be reproduced in the photo.

Eastman's

solution was to coat the paper with a layer of plain, soluble gelatin, and then

with a layer of insoluble light-sensitive gelatin. After exposure and development, the

gelatin bearing the image was

stripped from the paper, transferred to a sheet of clear gelatin, and varnished

with collodion -- a cellulose solution that forms a tough, flexible film.

As he

perfected transparent roll film and the roll holder, Eastman changed the whole

direction of his work and established the base on which his success in amateur

photography would be built.

He later

said: 'When we started out with

our scheme of film photography, we expected that everybody who used glass

plates would take up films. But we found that the number which did so was

relatively small. In order to make a large business we would have to reach the

general public.'

Eastman's

faith in the importance of advertising, both to the company and to the public,

was unbounded. The very first

Kodak products were advertised in leading papers and periodicals of the day --

with ads written by Eastman himself.

Eastman

coined the slogan, 'you press the button, we do the rest,' when he introduced

the Kodak camera in 1888 (his patent was awarded September 4, 1888) and within

a year, it became a well-known phrase. Later,

with advertising managers and agencies carrying out his ideas, magazines,

newspapers, displays and billboards bore the Kodak banner.

Space was

taken at world expositions, and the Kodak Girl, with the style of her clothes

and the camera she carried changing every year, smiled engagingly at

photographers everywhere. In

1897, the word Kodak sparkled from an electric sign on London's Trafalgar

Square --one of the first such signs to be used in advertising.

Today,

company advertising appears around the world and the trademark Kodak, coined by

Eastman himself, is familiar to nearly everyone.

The word

Kodak was first registered as a trademark in 1888. There has been some fanciful

speculation, from time to time, on how the name was originated. But the plain

truth is that Eastman invented it out of thin air.

He

explained: I devised the name myself. The letter 'K' had been a favorite with

me -- it seems a strong, incisive sort of letter. It became a question of trying out a

great number of combinations of letters that made words starting and ending

with 'K.' The word 'Kodak' is the result.

Kodak's distinctive yellow trade dress, which Eastman selected, is

widely known throughout the world and is one of the company's more valued

assets.

Thanks to

Eastman's inventive genius, anyone could now take pictures with a handheld

camera simply by pressing a button. He made photographers of us all.

He was a

modest, unassuming man... an inventor, a marketer, a global visionary, a

philanthropist, and a champion of inclusion.

Eastman died

by his own hand on March 14, 1932 at the age of 77. Plagued by progressive disability

resulting from a hardening of the cells in the lower spinal cord, Eastman

became increasingly frustrated at his inability to maintain an active life, and

set about putting his estate in order.

Eastman was

a stupendous factor in the education of the modern world, said an editorial in

the New York Times following his death. Of what he got in return for his great

gifts to the human race he gave generously for their

good; fostering music, endowing learning, supporting science in its researches

and teaching, seeking to promote health and lessen human ills, helping the

lowliest in their struggle toward the light, making his own city a center of

the arts and glorifying his own country in the eyes of the world.

During his

lifetime, he gave away an estimated $75 to $100 million, mostly to the University of Rochester and the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology

(under the name of 'Mr. Smith'). The

Rochester Institute of Technology has a building dedicated to Mr. Eastman, in

recognition of his support and substantial donations. MIT has a plaque of Eastman (the

rubbing of which is traditionally considered by students to bring good luck) in recognition of his

donation. Eastman also made substantial gifts to the Tuskegee Institute and the

Hampton Institute. Upon his

death, his entire residuary estate went to the University of Rochester. His former home at 900 East Avenue in

Rochester was opened as the George Eastman House  International

Museum of Photography and Film in 1947. On the 100th anniversary of his birth in

1954, Eastman was honored with a postage stamp from the United States Post

Office.

International

Museum of Photography and Film in 1947. On the 100th anniversary of his birth in

1954, Eastman was honored with a postage stamp from the United States Post

Office.

In 1907,

Eastman's mother died, devastating him completely. His close relationship with Josephine

Dickman deepened after this, but, despite many

speculations about them marrying, he remained a life-long bachelor. He mellowed somewhat, though, and

became interested in philanthropy. He

gave huge donations to MIT, the Hampton Institute, the Tuskegee Institute, and

the Rochester University, creating the Eastman School of Music at the latter. He opened the Eastman Theater in

Rochester, with a chamber-music hall, the Kilbourn

Theater, in his mother's honor.

Information for this composure about George Eastman came from numerous

on-line searches. If you need URL

confirmation for any aspects, contact me for documentation.

Dwight Albert (D. A.) Sharpe

805 Derting Road East

Aurora, TX 76078-3712

817-504-6508